History of Erik Buell

Written by Court Canfield and Dave Gess, for the book 25 Years of Buell.

A good overview about how Erik Buell started. Written by Court Canfield and Dave Gess, for the book 25 Years of Buell.

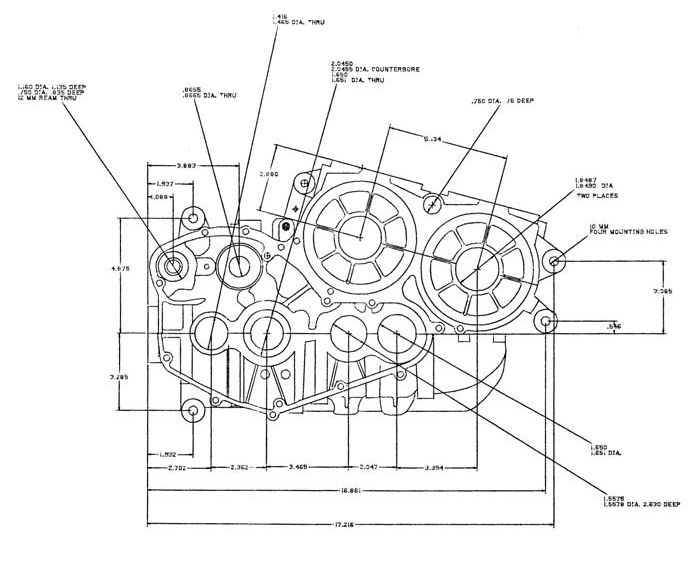

Buell set up a large drawing board in the “barn” so he could draw the RW 750 engine components.

The building was not really a barn—the barn was across the drive—but rather a large farm outbuilding with three garage

doors and a concrete floor.

Heat was by an antique oil burner that had its own small oil tank. Every day someone filled the tank bycarrying a pail to the 300 gallon outside tank, filling it and hauling it into the shop.

When it was really cold out it would be an hour before the coats came off.

An original drawing of the RW 750 crankcase produced by Erik Buell. This is part of the drawing that is on the drawing board in the picture below.

1979-1985 RW750 SILVER DREAM RACER

Erik Buell was born in 1950 in Gibsonia, Pennsylvania. His dad was a top notch patent attorney and his mom taught English.

(Don’t turn inany document to Erik with grammatical errors; it will come back with all the errors marked up!)

He was exposed to a lot of mechanical stuff on the farm; his dad collected interesting cars and by the 1960s his motorcycle passion was in full bloom. His first motorcycle ride at age

12 had ignited the flame that continues to burn today. By the late ’60s he’d begun working at bike shops and was racing motocross.

He worked for shops throughout the Pittsburgh area but perhaps the most important was the one belonging to Walter “Zero” Finnegan. Zero was a bit of a local legend, choosing to run his own small shop rather than use his considerable mechanical skills to work for someone else.

He was not a good fit for many of these shops as he was a meticulous craftsman and committed to giving customers the best service he could.

Erik took to heart Zero’s commitment to customer service and it bremains a guiding principle for Erik and Buell Motorcycles.

Erik had tried his hand at being a rock star—didn’t we all at that age—but it was tough to make any money. The baby boomer explosion in the motorcycle marketplace was well underway and competent mechanics were in demand. Seriously good mechanics could make some real money.

Erik was one of the good ones. He essentially turned himself into an independent contractor, working for whichever shop needed a top-notch wrench.

He could work on any brand and usually could beat the book rate while doing first class work.

If the shop asked him to do something he considered unethical, he would simply move to another shop. The fellow who wanted him to clean-up and quiet down the little Hodaka comes to mind.

This dealer planned to sell it to some sucker as a 4-speed. It had come from the factory as a 5-speed but the tranny was failing. Erik refused to fake it and walked. Some shops were a little rough.

At one, a customer showed up with a shotgun and the owners faced him down with the pistols they carried; Erik knew it was time to move on.

By the early ’70s the racing bug had bitten really hard and he was riding on the fire roads in the area for hours each day to train.

In 1972 he was running his F81M Kawasaki hard on a fire road when disaster struck. He was flat out and sideways when coming the other way was a young kid on a little dirt bike. The kid froze.

Erik was running so hard he could not avoid a collision and took out the entire front end of the

bike with his leg. The front wheel of Erik’s bike was destroyed and his leg was crushed.

The forks bent backwards so far that they broke some

of the fins off the cylinders. With a shattered leg and bleeding badly Erik was lucky that a Jeep came along and got him to the ER before he bled to death. It was a close thing. When he was stabilized, one of the doctors wanted to amputate. Fortunately a different doc thought the leg could be saved. What pieces remained were screwed into a metal shaft and they casted Erik from the hip to the toes. That was the end of his motocross/flat track career. Instead, when he could finally get up and move around, he took the motor from his crushed bike and combined it with a 350cc cylinder

and a H1R Kawasaki frame to make a road-racing bike for a friend.

They made it to Daytona in 1973 but shortly afterwards the fellow decided he wanted out.

Erik bought the half his friend had provided and went road racing. He had realized that even though he could not race motocross with a cast he could get on a road racer. He turned out to be pretty good, running at the front of a Novice class that included the likes of Dave Roper, Richard Schlacter, and Dale Singleton. He saw Gary Scott beat Kenny Roberts at Laconia on the Harley-Davidson RR250 GP bike and when they became available for purchase he just had to have one.

He borrowed a lot of money to buy one and when it showed up for the 1974 season, it was horrible. The production version was not even close to the bike Scott rode; they were unreliable and to top it off you couldn’t get spares.

Erik watched in frustration as the fellows he had diced with as a Novice continued to

win races and qualify for Expert while his bike would break and he would slide further down the list. Perhaps the low point of the season was the Talladega round.

He had crashed the RR again by pushing too hard in a valiant but fruitless effort to make a slow bike go fast, and had a white gel-coated Yamaha fairing mounted on the bike (you couldn’t buy a Harley-Davidson fairing). No paint, just a number. While driving all night to get to the race he stopped at a truck stop and saw a very large decal of a leaping bass.

You know the ones; they decorate the rear windows of campers all across America. Erik decided it was just the thing to brighten up the boring white gel coat. This decision may have had something to do with lack of sleep, but for whatever reason a pair of these beauties ended up on the bike. When he rolled the bike into tech, the inspectors took one look and flunked him.

They would not let him race until he took the decals off.

.jpg)

Pittsburgh Performance Products

Erik Buell was your typical racer: always struggling to get enough money for racing. The really good parts were expensive, so Buell, not content with just being a

consumer, decided to become the U.S. distributor, under the name of Pittsburgh Performance Products, for some of the products he wanted to use on his bike.

He got on board with manufacturers of the best equipment out there. He sold the very lightweight Dymag magnesium wheels, AP Racing brakes, and Interstate Leathers

(despite the name these were high quality race leathers made in England).

The exchange rate really favored the dollar so this was a very nice little business.

Buell also developed and patented a “sandwich” brake rotor. At the time brake rotors were either cast iron, stainless steel, or aluminum. Cast iron has excellent brake feel, good heat transfer, and good life but is prone to rust and is very heavy. Aluminum is very light and has excellent heat transfer properties but wears out quickly.

Buell addressed these issues in his patent application: “It has long been recognized that the removal of even a few ounces of unsprung weight was of tremendous advantage.”

“I have discovered a brake disc which solves all these problems. It is light in weight, has high thermal transfer characteristics, and is highly resistant to the wear and abrasion of the brake pucks.” Buell’s solution was to sandwich an aluminum core between two sheets of stainless steel. They had one-third less weight than a steel rotor plus much better heat transfer and a very long life. The Wilke Brothers’ race team won two USAC National Midget Championships in the

Sales literature was produced for the products Buell sold through his Pittsburgh Performance Products company to support his racing.

1980s using just one set of brake rotors for an entire year. One of the points that Buell stressed for the Dymag wheels and the Buell Brakes was the reduction in rotational mass and unsprung weight.

You can see from the ads that Buell’s current ZTL brake system is not just “marketing speak” but a further development of a long-held belief.

Barton Motors

Barton was a tiny company founded in the mid-1970s to produce an English Formula One motorcycle. Most of the Japanese Formula One bikes were run by teams

located in England so there was a lot of expertise available to make parts.

The engine was derived from a Suzuki. The first, and apparently only, complete bike

they built was for the movie “Silver Dream Racer” which starred David Essex.

The chassis followed common wisdom at the time that too much stiffness was not good, and that the right amount of flex in the chassis would result in a nice-handling motorcycle.

This sometimes actually worked for the underpowered, skinny-tired bikes of the early two-stroke era but with the power the 750 Barton was making by 1981, a flexible frame was almost unridable.

This brochure for the Barton company shows the Silver Dream Racer bike that was featured in the movie of the same name. The primary function of racing tech inspection is to ensure the safety of the participants; secondary functions involve meeting the basic rules of the class you are running.

They are not trying to catch

cheating—if you have used the valve springs from a 1936 Super Duper while only 1935 valves are allowed, the post-race teardown is supposed to catch that.

They also enforce standards involving appropriate decals and the like but safety is the first and foremost task of the inspectors.

Imagine his surprise when Erik rolled his bike back to the pits to ready it for the first race only to find that the frame was cracked in three places. Seems it was okay if his bike folded in half at 150 mph but it was not gonna have a big old bass on the side when it crashed!

In the mid ’70s, to help raise money to support his racing and also to cut costs for parts, Erik set himself up under the name of Pittsburgh Performance Products as a distributor for some of the parts he needed. This enterprise would prove to be a lifeline at key points in the future.

While Erik was chasing his road racing dreams and wrenching at bike shops he was also pursuing a mechanical engineering degree at the University of Pittsburgh.

As he worked his way through school he also worked his way up the ranks of AMA road racing. He made Lightweight

Expert in 1977 and Formula One Expert in 1978. He graduated from Pitt with a Mechanical Engineering degree in 1979. Harley-Davidson

Harley Davidson

Erik had done well in school and his look of steely determination surely did nothing to discourage potential employers, so he had his choice of a few jobs including a very nice one in aerospace. Instead, he pursued Harley-Davidson. They were the only American motorcycle company and Erik had it very bad for motorcycles. Harley-Davidson would only recruit locals and were not all that big on college grads. Erik had to get himself to Milwaukee and talk his way in.

That he did, and once there his talent and drive quickly made an impact.

He started out doing testing and analysis; his first job was tracking the oil usage on Shovelhead test bikes. This consumed a lot of time as you might imagine. Shovels were never known for being oil-tight. He quickly rose through the ranks to lead the chassis development team for the FXR project. His personal racing was also in progress. He owned and raced a Ducati and a TZ750 Yamaha, the latter running in the old Formula One (F1) class.

His racing program was moving along fairly well for a couple of years but things were about to change.

The career at Harley-Davidson was going well. He was leading the chassis team on the FXRT project and as a result learning an enormous amount about real world motorcycle chassis dynamics.

The team hooked up test bikes with recording gear and then flogged them around the Talladega test track, recording what was happening. The result was

one of the sweetest handling Harleys of all time (these bikes became one of the favorite rides of the Hell’s Angels because of this), and a head full of knowledge that Erik would find useful for years to come. Erik’s career was going well but his racing was not.

He was fast but the Yamaha was old and wearing out. He was also concerned about racing a Yamaha while Harley-Davidson was locked in a life-anddeath struggle with Japanese manufacturers; it was becoming increasingly obvious that racing a Yamaha while working for Harley was not appreciated by people in the corner offices. Erik considered two solutions to these problems.

The first involved an obscure British company called Barton Motors, which had built a 750cc square four two-stroke race bike. The second involved convincing Harley-Davidson that they should take the Sportster motor and build themselves a real sportbike.

This dyno chart is from an RW 750 run that was made to tune the exhaust pipes. By this time there was more Buell than Barton in the engine.

It gains over 23 hp in less than 600 rpm when you hit 7500 rpm; ultimately gaining 90 hp in 3000 rpm to reach 163.5 hp at 10500 rpm. This is manageable in a race car with nice fat slicks but trying to feed in throttle while leaned over on a bike was treacherous.

Even with modern slicks this would be a handful; with 1980s tires it was a recipe for high sides. Buell was able to smooth it out a bit by tuning the pipes and carbs but it would never be an easy bike to ride. Before

Buell designed a nice stiff chassis, it bordered on the suicidal.

Carmine Vara and Erik produced these packets in an effort to attract sponsorship for what would eventually become the RW 750. They got no takers.

Erik was watching the ambitious Barton motorcycle, which costarred with David Essex in the B movie “Silver Dream Racer,” when the TZ’s chassis broke. The Barton looked to be the answer to his problems, so he bought the Barton bike in late 1980. Actually the bike was just the beginning of his problems. The second solution got about as far as you might imagine. It would reappear after the first solution collapsed but we will get to that later.

The Barton bikes had shown potential with 500cc engines but the larger 750cc displacement did nothing to help their already questionable reliability. In addition, the chassis was decidedly marginal. Not to disparage Barton—after all it was a couple guys in an ancient abandoned church attempting the impossible—but their lack of resources resulted in a motorcycle that was not going to take Erik into the upper reaches of the AMA pro ranks. However, it was fast. Erik felt he could fix the problems. He was, after all, very knowledgeable about motorcycle chassis design.

Did we say the Barton was fast? It was very fast. Erik would eventually get it to 178 mph with a peak horsepower of 163 at 10,500 rpm. This was more than enough to compete with the ubiquitous TZ750 in AMA F1 racing. There was of course one small issue. Its very flexible frame would wind and unwind itself under hard cornering. The result

was unpredictable handling. If the motor had given you a nice broad power curve, you could ride around the handling. Trouble was the power band was about as wide as a matchbook and when the power hit, all the matches lit at once. Plus, it liked to seize—often and without warning.

The thing was a wicked, mean, and nasty SOB but when it was right it had the power to kick the TZ750’s butt; a very seductive package for a determined young engineer/racer. With Carmine Vara, his friend and partner in the enterprise they called Ermine Racing, Erik struggled with the Barton through 1981 but the beast was constantly breaking. Erik was constantly calling England

for parts. They persevered, intrigued by its potential. Then fate intervened. In early 1982, Erik learned that Barry Hart (the mad Welshman behind Barton) had gotten a job offer from British bike maker Armstrong that he just could not refuse.

The idea of an actual steady income was too much to pass up so he took it. Barton parts would become unavailable. Erik, as he likes to do, jumped in with both feet, buying the whole Barton deal, lock, stock, and porous crankcase

castings. He really had little choice. If parts became unavailable, Erik would not have a bike to race in F1. Going back to race a production the Buell-Barton engine.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Not on Two Wheels

Bill Meyer in his Buell powered Ocelot at Road Atlanta for the 1985 SCCA National Championship races. Meyer was the last of the sports car guys to give the engine a try.

Meyer found the motor “reliable and fast.” He won the SCCA round at Summit Point in August, but at the National Championship races the ignition system failed. That was the last gasp for Dave Ammen and Greg Rutherford purchased Barton engines to use in a SCCA D-sports racer.

This class allowed 850cc engines of any configuration. The Barton had a real power advantage over other available engines but proved to be very fragile. “We were consistently faster than everyone else, but we could not get the engine to last,” Ammen said. “It needed more work and financial backing than we were able to give it.” Ammen had to make his own set of gears. “The gears were just not able to handle the weight of the car,” said Ammen. Fortunately he was in the business of making gears. He managed a couple of wins and qualified for the National Championships a few times but gave up after not being able to overcome the reliability issues.

The 750cc engine also saw use in Nigel Rollason’s sidecar rig at the Isle of Man TT and it is there that Barton had its best results. Rollason managed a second in 1979 and a first and third.

This advertisement for the sports in 1986. He was consistently fast from 1979 until 1987.

By the car motor ran in Sports Car time of his victory Buell owned Barton and some of the pieces in magazine. the winning chair were more Buell than Barton. bike after running in the premier class was not an acceptable option so Erik really had to buy Barton.

He was convinced he could make the business work and sell some motorcycles. There was a market for a decently- priced replacement for the TZ750 in AMA racing. It took until very late in 1982 to arrange all the details and then in early 1983 Erik wrote the check.

He was in the motorcycle business. Unfortunately, by the time the pieces all arrived, the 1983 race season was half over and valuable development time was lost.

Development of the RW 750

Erik labored on continuing to develop what was now being called the RW 750 motorcycle.

Then in the spring of ’84 he convinced Harley- Davidson to witness a test at Talladega (a track where Harley- Davidson rents countless hours of testing time) hoping to get them to take the project under their wing and get him the resources to compete

It usually looked like this in the shop at the farm, where you can see one partially assembled RW 750 and one bare frame.

When the first “production” RW 750 was finished, Erik Buell and Dave Gess set up a photo shoot. Dave had access to a portrait studio at that time; it was decidedly marginal for what he had in mind but when you have no money, you have to make it work. (Making it work was a recurring Buell theme!) Dave borrowed yards of black velvet material from a photographer friend and draped the studio in it. Two exposures were taken, one with the bodywork off and one with it on.

The result is this ghost image. Erik would later credit this picture as the inspiration for the translucent bodywork on the City-Cross model of 2005.

.jpg)

in the Daytona 200. Doug Brauneck would ride the bike, Erik would wrench, and Harley-Davidson would watch. They offered no money to help the test along so Erik arrived on his usual shoestring. Brauneck ran a dozen laps and was very fast indeed. A speed of 178 mph was recorded on the radar gun and the handling was great. His speed was such that Harley-Davidson began to believe that running competitively at Daytona was not a fantasy.

They wanted to see just how the bike would do over 200 miles. This seemingly delightful result of the test was the RW’s downfall.

Because of the time constraints Harley needed to run the test that weekend. The only tires available that would survive the banking for

any length of time lowered the bikes gearing. Erik, being broke, did not have any gears that would allow the bike to run fast and stay below red-line on the Talladega banking. Brauneck ran some very, very fast laps. The engine seized. Erik fixed it. It seized again.

Turned out one of the rotary valves was incorrectly machined and that cylinder was leaning

out at maximum rpm. Harley was not happy; Erik was still on his own. Now a regular guy like you or I might say at this point “Damn, that didn’t work. Glad I have a day job to pay the bills.” Erik is not a regular guy. He decided that if he had more time he could get this thing working right and have bikes to sell by the fall. To get the extra time he quit a

very nice job at Harley-Davidson. (Actually, he tried to quit, but Jeff Bleustein made him take an extended leave of absence so he would

The RW 750 engine was a 66.4 x 54.0 mm bore and stroke, rotary valve square four. It featured two twin-cylinder crankshafts geared together. There are four separate cylinders. Many of the parts were designed or redesigned by Buell, including the pistons and the flywheel. The engine started life as a 500; there was also an 850 version in addition to the 750 that Buell raced.

Doug Brauneck on the RW 750 prototype during practice at Road America in 1984.

Road America

By the summer of 1984, Buell had fixed most of the RW’s problems and was running the bike in as many AMA Nationals as he could afford. The goal was to sell bikes.

At Road America that year Doug Brauneck, one of the top privateers, was entered to ride the bike. He did a lot of practice laps and was impressed, but he was concerned about reliability and, at the very last minute, decided to stick with the slower but reliable Yamaha TZ750.

Erik literally jumped into his leathers and ran to the start line. He only completed one lap before the water pump drive sheared. Dave Gess managed to get one shot of him aboard the bike.

The next race was at Pocono. On the Monday before the race, Buell joined a few friends who had rented Blackhawk Farms race track outside of Beloit, Wisconsin, and ran a

few laps to make sure he had fixed the water pump problem.

The bike ran great until it Erik Buell and John Hasty discuss the RW. seized in turn one and highsided Buell to the ground. He broke three ribs. The bike did not run at Pocono.

The one-car garage in Milwaukee, where Erik started to develop the RW 750, became increasingly difficult to work in as the RW 750 project grew. This farm near Mukwonago, Wisconsin, was a perfect location for the project. The barn itself, on the left, was used for storage of leathers, wheels, and general parts. The small building in front of the barn was the office.

It may have started life as a milking shed and is attached to the barn.

The out-building on the right was the actual “factory” where the RW 750 was made and early RR 1000s were built. have the option of coming back after six months.

He was not coming back.) His parting was on exceptionally good terms—something that would prove important in the future.To develop a race bike Erik needed cash, so he sold his duplex and found a run-down farm to rent in Mukwonago, Wisconsin. The farm was a long way from any neighbors and had a nice garage building as well as a barn. It was an ideal place to build and test a race bike. He would generate some income by stepping up his Pittsburgh Performance Products business.

The RW 750 really was, as the hot rodders say, “sanitary.” Lots of attention to detail is evident in the construction of the chassis. It had mostly straight tubes for maximum tiffness.

The engine was mounted well forward to keep weight on the front end. The front suspension was Marzocchi with the patented Harley-Davidson electro-pneumatic anti-dive system (which Erik invented). The rear suspension was a single Works Performance unit.

The axles were thicker than usual 1980s practice; the front was 20 mm versus the usual 17 and the rear was 25 mm versus 20. The bearings were out against the fork tubes. None of this was common 1980s practice but resulted in a much stiffer axle. Increasing

stiffness is a theme continued across the entire history of Buell motorcycles. The bodywork not only looked good but shows the beginnings of Buell’s interest in aerodynamics.

It started with the basic shape of the 1969 Harley-Davidson Cal Rayburn streamliner developed in Cal

In the winter of 1984-85 Kevin Cameron authored a feature story for Cycle magazine. This portrait was taken for that story. You can really see the pride radiating from Erik Buell as he poses with the RW 750. Tech’s wind tunnel. Careful attention given not only to airflow over the bodywork but also through the radiators resulted in a very efficient, aerodynamic package.

At the time, most fairings were simply covers, with little attention paid to how they actually worked moving through the air. Some period race bikes were faster without the fairings.

By 1984, the new bike was ready and media kits went out. Cycle magazine sent Kevin Cameron out to write a major feature article that appeared in the July 1985 issue. One bike was sold and a second sale was pending. It looked like the gamble was going to work. America had a new motorbike company. Then, in spring of 1985, the AMA pulled

the plug on the class. Formula One would go away and the growing Superbikes would become the premier class. Overnight Erik’s market was gone and along with it his business.

Alan Ladd aboard the Machinist Union RW 750 prepares to go out for practice at Daytona. Ken Winpisinger is standing at the left.

Machinist Union Bike

One RW 750 was sold. On January 14, 1985, this was delivered to Kenneth Winpisinger of the Machinist’s Union. “Alan Ladd and I had been racing locally and winning a lot,” said

Winpisinger. “My dad was president of the Union and they sponsored an Indy Car team.

I’m thinking to myself ‘they should sponsor us’ and then I saw a magazine story on the Buell

and showed it to my dad over dinner. The Union was always looking to promote American-made products. I jokingly told Dad, ‘I should get one of these and you guys sponsor us.’ He said ‘Go get it.’ I just about fell over. I called Erik and bought one.” The plan was to run the 1985 AMA season which kicks off at Daytona.

“It would be better to start a new race program somewhere other than Daytona,” said Winpisinger,

“if you are not 100 percent ready to go, that place will hurt you.” It certainly did hurt them.

The bike seized in practice out on the banking between NASCAR turn three and four.

Top gear was about 160170 mph. Ladd managed not to crash and they got the motor back up and running by race day. “What I didn’t realize at the time was the amount of damage done to the rest of the engine when it seized. We kept having issues at the next several races and it finally dawned on me that they all could be traced back to that seizure. There was a lotta stuff we should have done right away that we didn’t think about. It was a learning curve for all of us, that’s for sure,” Winpisinger said.

The bike did not qualify at Daytona but they were told to be on the grid to replace any non-

starters. A few guys didn’t make the race but the AMA official at the line straddled the front tire and grabbed the faring not letting them go out. He actually wrenched the fairing so hard he cracked it. They never ran a lap. To add insult to injury they were listed as 80th, last place in the official results posted the next day. “I was furious, they wouldn’t let us start and then they said we finished last,” said Winpisinger. The best finish all year was second in a club race at Summit Point at the end of year. “I felt we had a pretty good package by the end of the season and was confident that we would have done well if the class had survived,” Winpisinger said. “It was very frustrating.